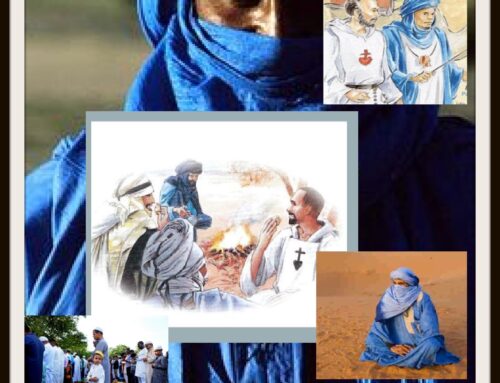

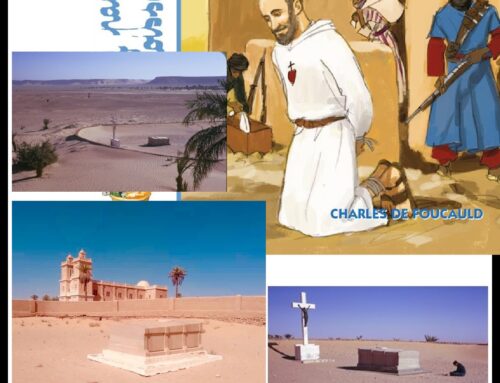

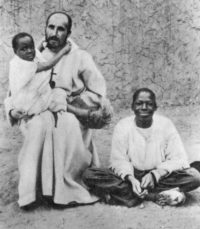

Seven months after its occupation by France, the well worn Sandals of Charles de Foucauld entered Béni Abbès, “the largest palm-forest of the Sahara.”[1] Here he came face-to-face with the African slave market. The trade of humans had been centuries old. Charles observed that the slave’s “material poverty is extremely great [and] their spiritual poverty even greater.”[2] A zeal for justice blazed his already inflamed heart. He addressed it in his letters, writing, “There is no other remedy to this shame and this injustice than the setting free of the slaves.”[3] His written words were not enough, they had to incarnate themselves. Burning love took on flesh when de Foucauld purchased a few children out of slavery. Those liberated included Paul Embarek, who would later be present at his death.

The extravagant zeal for justice that engulfed Charles’ heart has poured into the spirituality of his followers. It is expressed in The Little Guide. To imitate the life of Jesus is not to support unjust evil systems. Against such structures “We do not have the right to be silent watch dogs,” writes Charles; “we must cry out when we see evil being done.”[4]

The extravagant zeal for justice that engulfed Charles’ heart has poured into the spirituality of his followers. It is expressed in The Little Guide. To imitate the life of Jesus is not to support unjust evil systems. Against such structures “We do not have the right to be silent watch dogs,” writes Charles; “we must cry out when we see evil being done.”[4]

We must cry out.

What does it mean to cry out? My initial thought is the Battle of Stirling in Braveheart, when William Wallace (Mel Gibson) leads thousands of blue skinned Scotsmen rushing into battle crying out all the way. I have recently reflected upon a different kind of crying out. It is when one’s life itself cries out. A life that cries out the good news of God’s kingdom is de Foucauld’s quintessential credo. To cry out the Gospel with one’s life is when an act of kindness to another speaks, or when the activity of being patient is itself that word that speaks God’s goodness.

As wood heats to produce the visible light of fire, so there is a more hidden, quiet crying out that goes before such visible actions. This gentle heat burns in the heart for authentic works of justice.

On Ash Wednesday, I walked up the stairs of the hospital to meet my wife for an ultrasound. I was coming late from work and I hoped to catch the procedure’s last minutes. Passing a television on the wall, I caught the news. There was a mass shooting at a High School in Florida. While helicopters churned the air above, children rushed through school doors, past police armed with assault rifles, and into the arms of crying parents. The tears of sons and daughters mingled with the tears of anxiously awaiting moms and dads.

The Friday following, I walked between empty wooden pews and the Stations of the Cross that hang upon my parish walls. I arrived at the 8th station, when Jesus meets the holy women of Jerusalem. St. Alphonsus Liguori’s words wrenched my heart:

Consider that those women wept with compassion at seeing Jesus in so pitiable a state, streaming with blood, as He walked along. But Jesus said to them, “Weep not for Me, but for your children.”

Weep for your children. There is a hidden, quiet crying out.

Jesus’ words did not guide me to weep directly for my sins and failures, but rather to weep and cry out in my heart for the suffering this week. I felt deeply the increased sorrow that has weighed humanity for so long. Genesis 3:16 has been on my mind. “To the woman he said, “I will greatly multiply your pain in childbearing.” Often this passage is understood as the physical birth pains of childbirth. It is more than the physical. When we look closely at the original Hebrew, we can see that the it can be understood as “I will greatly increase your sorrowful conceptions.”[5] Immediately, my mind goes to the sorrowful conceptions that are miscarriages, children with severe disabilities, and those who face other countless tragedies. Though there is joy in every life, we can’t ignore the sorrow. Like one stepping down a declining shore into deeper waters, we must enter into sorrow courageously.

This hidden, quiet, sorrowful crying out that occurs deep in our spirit in an empty church or crowded street is our heart drawing towards the infinite chasm of the weeping heart of Christ. In this drawing closer, we also draw closer to that sweet heart of Mary which was pierced, too (Lk. 2:35). As the Spirit draws our sorrowing hearts closer, we enter into the very heart of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The sorrow in our heart becomes Christ’s crying out. Our pain is transfigured in his historical passion that has echoed beyond the constraint of time. Our today is his Eternal Today. We are one with him on the cross. “I no longer live, but Christ lives in me,” writes St. Paul (Gal. 2:20). Jesus’ heart is mystically, eternally close to the Heart of the Father.

Into his sorrowful heart and back again we come to comfort a sorrowing world. “Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted” (Mt. 5:4). Our hearts are comforted by Christ with hope. As St. Paul writes: “Praise be to the God and Father of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Father of compassion and the God of all comfort, who comforts us in all our troubles, so that we can comfort those in any trouble with the comfort we ourselves receive from God. For just as we share abundantly in the sufferings of Christ, so also our comfort abounds through Christ” (2 Cor. 1:3-5). What is this comfort (παρακαλέω)? It is that we are “called close” to the “Father of compassion.” Jesus calls the Holy Spirit the Paraclete (Jn. 14:16, 26). He is the Comforter, the one who calls us close to the Father through the Son.

This entering into the Heart of God through sharing abundantly in the sufferings of Christ and being sent back again as agents of comfort for a sorrowing world makes us apostles of comfort, apostles of the Comforter.

Your brother,

Gabriel

Seattle, Wa.

Footnotes:

-

- Carrouges, Michel. Soldier of the Spirit: The Life of Charles de Foucauld. G.P. Putnam’s Sons (1956), pg. 157.

- Ibid., pg. 170.

- Ibid., pg. 157.

- Ibid., pg. 173.

- For more see the following article: Eves’s Curse Revisited: An Increase of Sorrowful Conceptions. Bulletin for Biblical Research (Volume: 26, Issue: 2)